If you've ever stood in an LNG control room, you know the hum of machinery is only half the story—a digital symphony of numbers flickers across screens, each one tracing its ancestry to a different corner of 19th-century physics. I remember the first time I shadowed a control engineer: he pointed to a cryptic readout, then—grinning—quipped, 'That's Carnot smiling down on us.' What sounds like an in-joke turns out to be the heart of why cryogenics works at all. This article dives into the stories—and the stubborn physics—that quietly power the liquid fuel revolution.

1. From Theory to Thermometer: Kelvin, Joule, and the Birth of Cryogenic Imagination

The story of industrial cryogenics begins not in a laboratory full of pipes and compressors, but in the minds of 19th-century physicists who dared to ask: what is temperature, really? Before the era of cryogenic temperature control and massive LNG plants, temperature was a subjective sensation—cold or hot, more or less. This changed dramatically with the work of William Thomson, better known as Lord Kelvin, and James Prescott Joule, whose discoveries laid the foundation for all modern cryogenic technology.

Kelvin’s Absolute Revolution: Measuring the Unmeasurable

Lord Kelvin transformed our understanding of temperature by introducing the absolute temperature scale. He defined absolute zero (0 K) as the point where all molecular motion ceases—the lowest possible energy state. This was more than a new way to read a thermometer; it provided a solid, universal reference point for all thermodynamic principles. Suddenly, temperature was not just a feeling but a number, a property that could be measured and calculated. As Kelvin famously said:

"If you can measure that of which you speak, and can express it in numbers, you know something about it; but if you cannot... your knowledge is of a meager and unsatisfactory kind."

Kelvin’s absolute scale made it possible to set precise targets for cryogenic temperature control. For example, the liquefaction of methane—a key step in LNG production—requires reaching 111.7 K. Without Kelvin’s scale, such precision would be impossible.

Joule’s Brewery and the Birth of Quantifiable Energy

While Kelvin gave us a way to measure temperature, James Prescott Joule taught us how to measure energy itself. In his now-famous brewery experiments, Joule used paddle wheels to stir water, meticulously tracking how mechanical work converted into heat. He established the mechanical equivalent of heat, quantifying it as 4.186 joules per calorie. This discovery formed the backbone of the First Law of Thermodynamics—energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed.

Joule’s work turned heat and work into two sides of the same coin. Engineers could now calculate exactly how much energy was needed to reach and maintain cryogenic temperatures. This shift from speculation to calculation was a turning point in industrial cryogenics advancements.

From Theory to Practice: The Engineer’s Toolkit

With Kelvin’s and Joule’s breakthroughs, thermodynamics became practical. Engineers gained the tools to design systems that could reliably achieve and control extreme cold. Imagine, for a moment, Sadi Carnot and Lord Kelvin debating over coffee: Carnot arguing about the limits of efficiency (entropy), Kelvin insisting on the importance of absolute zero. Their theoretical discussions would soon give rise to real-world innovations—refrigeration cycles, heat exchangers, and the precise monitoring systems that define today’s cryogenic technology.

These early steps—defining absolute zero, quantifying energy, and moving from subjective to objective measurement—made possible the precise cryogenic temperature control that powers the modern LNG industry.

2. Cathedrals of Cold: Efficiency, Entropy & the Limits of Refrigeration

The journey from theoretical thermodynamics to industrial cryogenics is anchored by two central concepts: efficiency and entropy. These ideas, introduced by Sadi Carnot and Rudolf Clausius, continue to shape every modern LNG liquefaction plant, where the quest for LNG liquefaction efficiency is both a scientific and economic imperative.

Carnot’s Formula: The Efficiency Ceiling

Sadi Carnot, in the early 19th century, provided the first mathematical description of how efficiently any engine—or, by extension, any refrigeration cycle—could operate. His famous formula:

η = 1 – T_c / T_h

where η is efficiency, T_c is the cold reservoir temperature, and T_h is the hot reservoir temperature (both in Kelvin), sets a hard upper limit. For LNG, where methane must be cooled below 111.7 K, this formula exposes just how much energy must be invested to push heat “uphill”—from cold to hot. The closer a process gets to Carnot’s limit, the less energy is wasted, but the cost and complexity rise sharply.

Clausius, Entropy, and the Second Law

Rudolf Clausius deepened this understanding by introducing entropy and formalizing the Second Law of Thermodynamics. His equation:

dS = δQ_rev / T

expresses how every bit of heat moved at a given temperature increases the system’s entropy. Clausius’s insight—“heat cannot flow from cold to hot without external work”—is the very principle behind all refrigeration. As Clausius famously said:

"The fundamental laws that govern the universe are remarkably simple; it is we who choose to complicate them."

In LNG plants, entropy calculations now drive every design choice, from selecting refrigerants to arranging heat exchangers.

The Cascade Refrigeration Process: Beating Single-Cycle Limits

Early engineers quickly realized that single-cycle refrigeration was a dead end for deep cryogenics. The solution was cascade refrigeration: using multiple refrigerants, each operating at different temperature stages, to stepwise extract heat. This approach, still central to cryogenic engineering innovations, minimizes thermodynamic losses and allows plants to approach the elusive Carnot efficiency. Modern LNG mega-trains use multi-stage and cascade processes, where even a 1% gain in efficiency can mean millions saved annually.

Designing the 'Carnot Prize'

If there were a “Carnot Prize” for creative cryogenic workarounds, it would go to the pioneers who turned theory into practice. From the first cascade systems to today’s optimized mixed-refrigerant cycles, each leap reflects a direct response to the limits set by Carnot and Clausius. The relentless pursuit of near-Carnot efficiency is not just a technical challenge—it’s a driver of profitability and sustainability in the LNG industry.

LNG liquefaction efficiency is fundamentally limited by thermodynamic principles.

Entropy calculations guide every process optimization.

Cascade refrigeration process is the key innovation that made industrial cryogenics possible.

3. The Tinkerers’ Leap: From Lab Curiosities to Cryogenic Powerhouses

The transformation of cryogenics from scientific curiosity to industrial powerhouse began with a handful of inventive minds and a few pivotal breakthroughs. The late 19th century saw the first true cryogenic engineering innovations, as researchers moved beyond theory and into the realm of practical, scalable technology.

Pictet and Cailletet (1877): The Birth of Gas Liquefaction Cycles

In 1877, Raoul Pictet and Louis Cailletet independently achieved the first liquefaction of oxygen—a feat that marked the real birth of industrial cryogenics advancements. Using intense compression followed by rapid expansion, they managed to cool gases to the point of liquefaction. What began as laboratory stunts quickly evolved into the foundation of modern gas liquefaction cycles. Their methods—especially the use of staged compression and expansion—demonstrated that the manipulation of pressure and temperature could unlock new states of matter, setting the stage for future cryogenic processing innovations.

Linde’s Breakthrough: Vapor-Compression and Counter-Current Heat Exchangers

The next leap came from Carl von Linde, whose work in the 1890s fundamentally changed the landscape of industrial cryogenics. Linde’s key insight was to combine vapor-compression refrigeration with counter-current cryogenic heat exchangers, allowing gases to be pre-cooled by their own outgoing cold streams. This process made large-scale air liquefaction not only possible but commercially viable.

Linde’s ‘aha’ moment, as legend has it, was inspired by observing a double-paned window frosting up during a harsh Bavarian winter. He realized that the same principle—using a cold surface to pre-cool incoming air—could be applied to industrial gas processing. This simple yet powerful idea became the backbone of his air liquefaction plant, which began operation around 1895.

"Innovation is the ability to see change as an opportunity, not a threat." — Carl von Linde

The Hardware DNA of Modern Cryogenic Plants

The evolution of compressors, expansion valves, and cascade processes during this era created the essential hardware toolkit for cryogenic engineering. These components—still found in every modern LNG plant—form the DNA of today’s cryogenic technology:

Compressors: Increase gas pressure for efficient cooling and liquefaction.

Expansion valves: Enable rapid cooling by allowing high-pressure gas to expand and drop in temperature.

Cascade cycles: Use multiple refrigerants or stages to reach progressively lower temperatures.

Counter-current heat exchangers: Maximize energy efficiency by recycling cold energy from outgoing streams.

Linde’s innovations are the direct ancestors of today’s advanced cryogenic heat exchangers and modular cold boxes. By the turn of the 20th century, these breakthroughs had enabled the commercial scaling of cryogenic processing, moving the field from isolated laboratory curiosities to the heart of global industry.

4. Leiden’s Ice Magician: Onnes, Vacuum Flasks & Quantum-Edge Cryogenics

In the early 20th century, the race to reach ever-lower temperatures found its champion in Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, the “Ice Magician” of Leiden. In 1908, Onnes achieved what many thought impossible: he liquefied helium, plunging below the 4.2 K barrier and opening a new frontier for cryogenic temperature control. This breakthrough did not just set a record—it transformed the landscape of cryogenic engineering innovations and laid the groundwork for quantum cryogenics advancements that still shape today’s technologies.

“Door meten tot weten”: Measurement as the Key to Cryogenic Cooling Technologies

Onnes’s laboratory at Leiden was a model of precision and rigor. His motto, “Door meten tot weten” (“Through measurement to knowledge”), captured his scientific ethos. Every experiment was meticulously measured, and every variable was controlled. This obsession with accuracy drove several foundational innovations:

Vacuum Dewar Flasks: Onnes perfected the use of vacuum-insulated containers—Dewar flasks—to store and handle liquefied gases. This technology remains central to modern cryogenic cooling technologies, from industrial LNG storage to laboratory quantum experiments.

Staged Refrigeration: By using successive pre-cooling agents (liquid air, then hydrogen, then helium), Onnes pioneered the staged cooling approach. This method is now standard in cryogenic engineering, enabling efficient progression to ultra-low temperatures.

Refined Thermometry: Onnes developed highly accurate thermometers, allowing precise monitoring and control of cryogenic processes—an essential requirement for both industrial and quantum cryogenics advancements.

Superconductivity: A Quantum Surprise at Cryogenic Frontiers

In 1911, while exploring helium’s ultra-cold domain, Onnes made a discovery that would echo through physics: superconductivity. He observed that mercury’s electrical resistance vanished at 4.2 K—a wild, unexpected fruit of cryogenic exploration. This phenomenon, rooted in quantum mechanics, proved that new physical laws could emerge at extreme cold, fueling today’s quantum cryogenics advancements.

Legacy: From Leiden to the Quantum Age

Onnes’s laboratory practices—vacuum insulation, staged cooling, and precise measurement—are still the backbone of cryogenic engineering innovations. Modern quantum computing, for example, depends on dilution refrigerators and vacuum-insulated systems directly descended from Onnes’s techniques. Accurate cryogenic temperature control, essential for stable quantum bits (qubits), is a direct legacy of his work.

"Door meten tot weten" ("Through measurement to knowledge"). — Heike Kamerlingh Onnes

Imagine Onnes, cup of supercooled tea in hand, advising today’s quantum engineers: his insistence on rigorous measurement and careful control would feel right at home in the world of quantum cryogenics advancements. The ultra-low temperature frontiers he opened continue to inspire new discoveries, proving that the path from laboratory curiosity to industrial necessity is paved with precision, patience, and the relentless pursuit of knowledge.

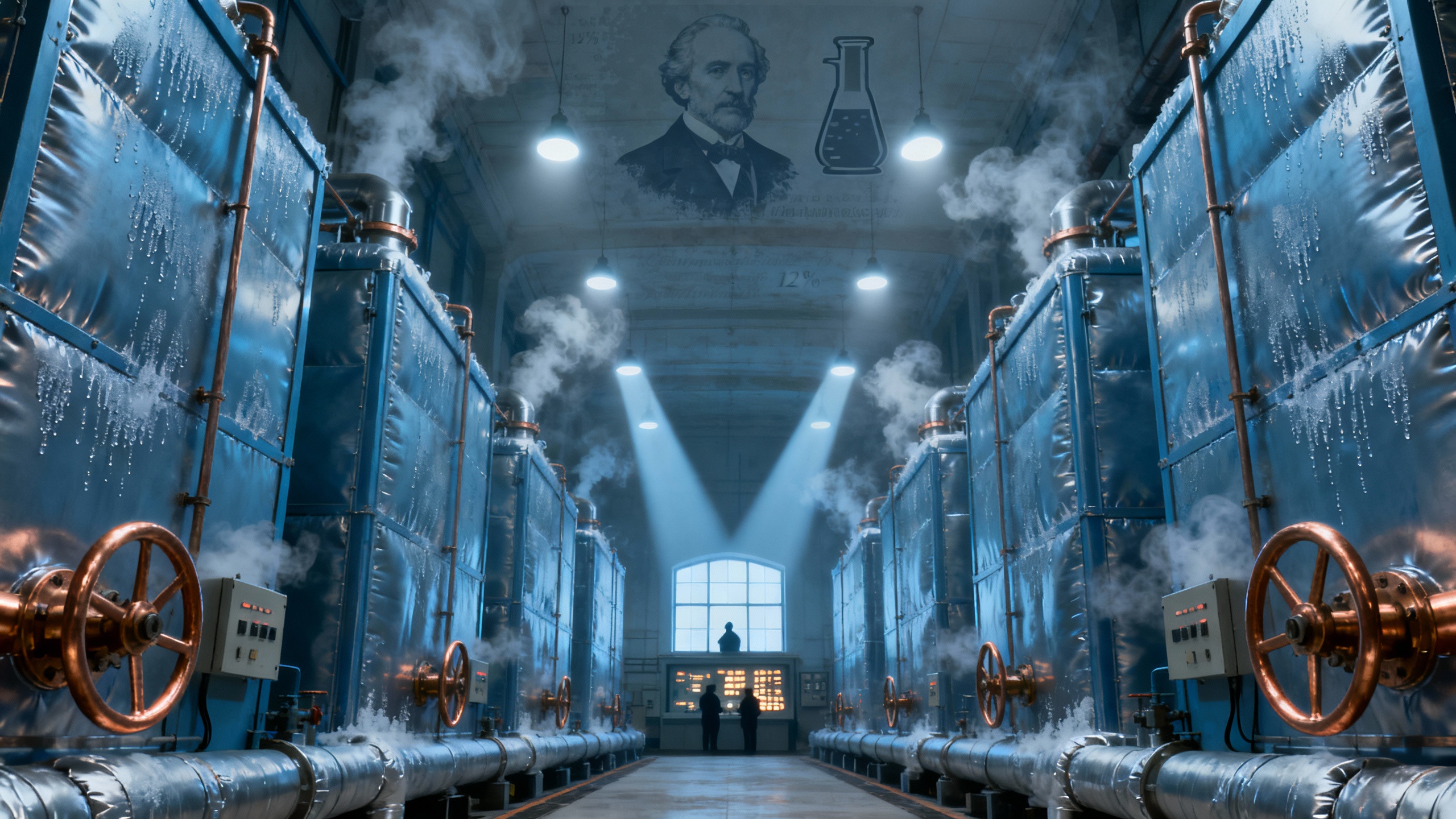

5. From Blueprints to Megatrains: Claude, Cold Boxes & the LNG Revolution

The modern landscape of LNG production processes is a direct evolution of breakthroughs in cryogenic engineering, with Georges Claude’s work-recovery expansion engine—known as the cryogenic turbo-expander—at its core. Unlike earlier methods that simply dropped gas pressure to cool it, Claude’s innovation extracted useful work from the cooling process itself. This meant that instead of losing energy, plants could recover it, turning what was once waste into valuable power. This principle of work-recovery expansion engines is now fundamental to the efficiency of large-scale LNG facilities.

Claude’s vision didn’t stop at the turbo-expander. He pioneered the modular “cold box”—a compact, insulated unit that integrates heat exchangers, turbo-expanders, and distillation columns. These cold boxes are more than just equipment; they are the heart of LNG plants, enabling precise control of temperatures down to the critical 111.7 K needed for methane liquefaction. Their modularity allows for flexible scaling and maintenance, making them a cornerstone of modern LNG infrastructure.

Today, the world’s largest LNG “mega-trains”—industrial plants capable of producing millions of tons of LNG per year—are built upon these foundational ideas. The ConocoPhillips Optimised Cascade process, for example, applies the classic cascade refrigeration process by using a series of pure refrigerants (propane, ethylene, methane) to cool natural gas in steps. Each stage is carefully matched to the cooling curve of the gas, minimizing energy loss and maximizing efficiency, in the spirit of both Carnot’s and Claude’s principles.

Similarly, the Air Products AP-C3MR and AP-DMR processes use mixed-refrigerant cycles, blending different gases to create a custom cooling profile. This approach, combined with advanced modular cold boxes and high-efficiency coil-wound or plate-fin heat exchangers, allows for unprecedented operational flexibility and energy savings. These innovations directly reflect the historical legacy of modularity and process optimization, now scaled up to meet global energy demands.

Walking through a modern LNG mega-train plant, one is struck by the sense of scale and precision. It feels less like a traditional factory and more like a cathedral dedicated to numbers and liquid methane. Every pipe, valve, and control panel is a testament to over a century of thermodynamic theory, now embodied in steel and sensors. As one industry saying goes:

"Innovation fuels the global energy transition."

From Claude’s turbo-expander to the iconic cold box, and from the cascade refrigeration process to today’s LNG mega-trains, each step in the journey has been about turning scientific insight into industrial artistry. The result is a global infrastructure that not only moves energy, but does so with unmatched efficiency—proving that the legacy of early cryogenic pioneers lives on in every drop of LNG produced.

Conclusion: Every Chilling Degree Is a Chapter of History—And a Promise for Tomorrow

The story of industrial cryogenics, and especially LNG liquefaction, is not just a tale of cold numbers or technical milestones. It is a living inheritance—a continuous thread stretching from the earliest days of thermodynamic theory to the mega-train LNG plants that define today’s energy landscape. Each chilling degree achieved in modern facilities is both a chapter of scientific history and a promise for tomorrow’s innovation.

Cryogenic temperature control, once a theoretical challenge, is now a practical reality thanks to the steady march of scientific progress. The ability to precisely reach and maintain temperatures like 111.7 K for methane liquefaction is the direct result of two centuries of purposeful discovery and engineering. The spectacular efficiency, safety, and scale of today’s LNG liquefaction efficiency are built on the shoulders of giants—Kelvin, Carnot, Clausius, Onnes, Linde, Claude, and many others—whose insights have been transformed into the very fabric of industrial cryogenics advancements.

Every operational parameter in an LNG plant, from compressor settings to heat exchanger temperatures, is a direct descendant of foundational thermodynamic principles. The process control systems that keep these plants running safely and efficiently are a synthesis of energy conservation (Joule), efficiency limits (Carnot), entropy management (Clausius), and measurement-driven rigor (Onnes). This seamless integration of theory and practice is what allows engineers to push the boundaries of LNG liquefaction efficiency, ensuring that every drop of liquefied natural gas is produced with maximum reliability and minimal waste.

Understanding the theory behind the numbers is not just an academic exercise—it is the key to smarter, safer, and more innovative engineering. Each calculation, each design decision, echoes with the voices of those who first defined the laws of thermodynamics. Their legacy is visible in every cold box, every turbo-expander, and every digital readout in a modern LNG control room. The continuity from theory to infrastructure highlights the immense economic and technological stakes of mastering cryogenic temperature control.

As the industry moves forward, ongoing innovation in industrial cryogenics draws strength from this deep well of knowledge. Every new process, every incremental improvement, carries with it the lessons and logic of the past. The numbers displayed on a control panel are more than just data—they are living proof of a collaborative history, connecting generations of scientists and engineers in a shared pursuit of progress.

And if one could invite a figure from cryogenic history to keynote a company’s annual conference, perhaps Heike Kamerlingh Onnes would be the ideal guest. His motto, “Knowledge by measurement,” perfectly captures the spirit of the field: a relentless quest for understanding, guided by careful observation and bold experimentation. In honoring such pioneers, the industry not only remembers its roots but also reaffirms its promise for a colder, brighter, and more efficient tomorrow.

TL;DR: Thermodynamic theory, from Kelvin's absolute zero to Onnes's vacuum flasks, built the backbone of industrial cryogenics. Their principles literally cool today's LNG—knowledge that matters every time natural gas crosses a global ocean as liquid.

Comments

Post a Comment