It started as a game of dares at the neighborhood ice rink, where everyone wanted to see who could keep their hand in a snowbank the longest. No one ever lasted more than a few seconds. Yet what began as a childhood contest sparked a lifelong question: What is the coldest possible cold, and who would dare to chase it? The answer, as this story reveals, isn’t just about scientific curiosity—it’s about inventiveness, dogged collaboration, and a dash of friendly rivalry, stretching across centuries and continents. Grab your scarf (and maybe a calculator), because we’re following an extraordinary cast of characters who dared to put numbers to cold—transforming abstract chills into the very pulse of today’s global energy network.

From Shivers to Science: The Dawn of Cold Measurement

Long before the glowing control screens of modern liquefied natural gas (LNG) plants displayed precise temperatures—273 K, 200 K, 150 K, 112 K—humanity’s relationship with cold was purely personal. “Brrr!” was the only language for a winter’s chill. But the journey from shivers to science began when early scientists dared to convert these sensations into numbers, laying the foundation for the entire history of LNG and the mastery of extreme cold.

Turning 'Brrr' Into Numbers: The First Thermometers

The first step in taming cold was inventing a way to measure it. Early thermometers, like those of Galileo and Fahrenheit, transformed subjective feelings into objective readings. This breakthrough gave scientists a universal language for temperature measurement, allowing them to compare results and repeat experiments. Suddenly, “cold” was no longer a vague feeling—it was a number everyone could agree on.

Lord Kelvin and the Absolute Temperature Scale

Imagine Lord Kelvin, hunched over his desk, sketching out scales with frostbitten fingers, determined to create a system that would work for all substances, everywhere. Kelvin’s great leap was the introduction of the Kelvin scale, anchored by the concept of absolute zero (0 K)—the coldest temperature possible, where all molecular motion stops. This was a game-changer for cold science and the future of LNG. As Kelvin famously said:

“When you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it.”

With the Kelvin scale, scientists finally had a finish line for their race to the coldest temperatures. 273 K became the new way to say 0°C, and absolute zero—0 K—became the ultimate target for cryogenic research.

Measurement: The First Step to Global Cold Mastery

The invention and standardization of thermometers and temperature scales did more than satisfy scientific curiosity. They made it possible to pursue colder and colder temperatures in a methodical, measurable way. This was the real first step toward global cold mastery and the birth of the LNG industry.

Reproducible Experiments: Scientists could now repeat and verify each other's work, accelerating discoveries.

Industrial Refrigeration: Accurate temperature measurement enabled the development of refrigeration cycles, crucial for liquefying gases.

Modern LNG Control: Today’s LNG facilities rely on precise temperature setpoints—273 K, 200 K, 150 K, 112 K—to safely and efficiently produce and transport liquefied natural gas.

Each number on a modern LNG display is a direct descendant of Lord Kelvin’s vision. These digits are not just operational parameters—they are the living legacy of centuries of scientific progress in temperature measurement, the Kelvin scale, and the relentless chase toward absolute zero. The history of LNG is inseparable from these chilly feats, where measurement was the true spark that ignited a global industry.

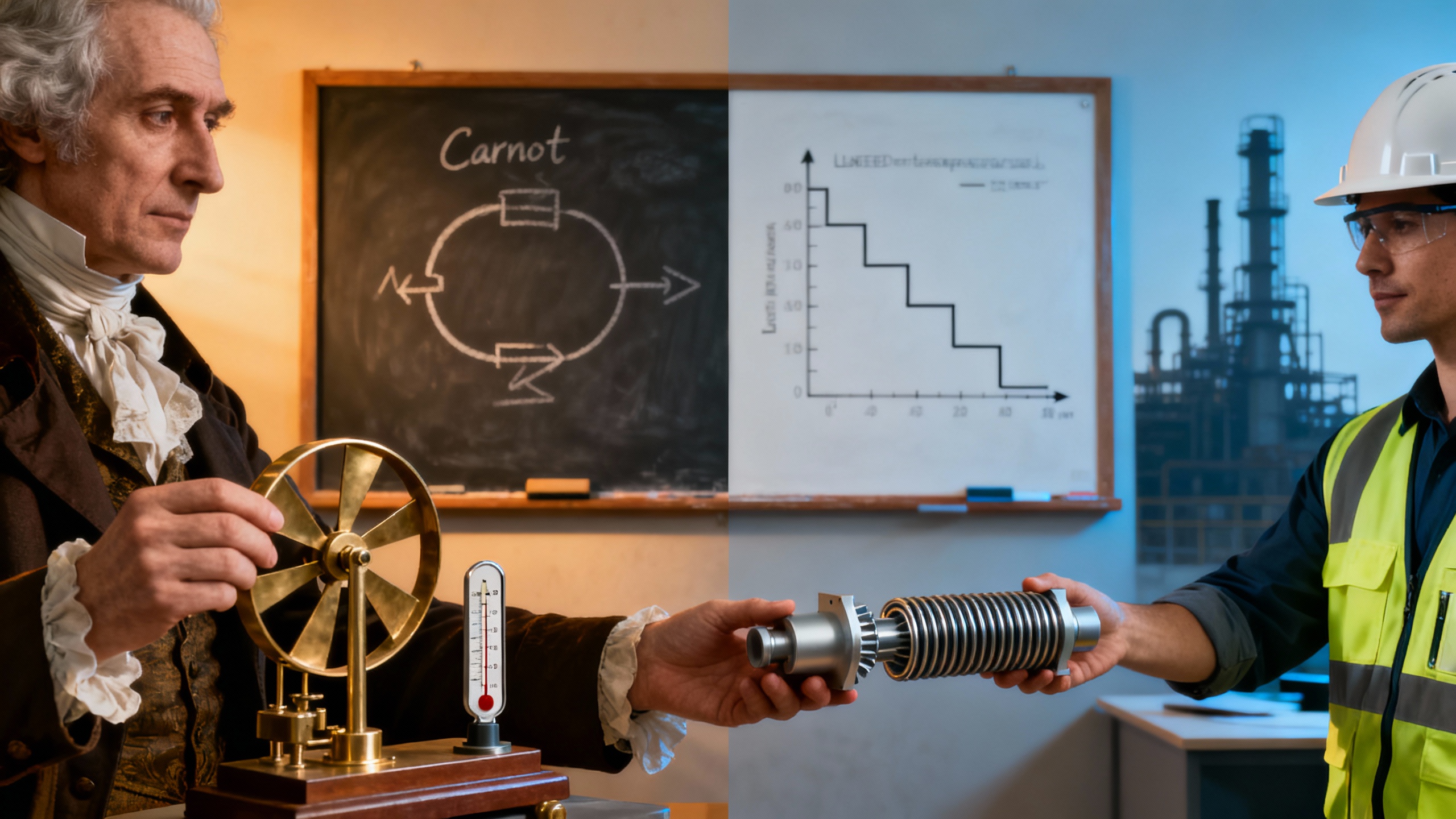

From Equations to Energy: Joule, Carnot & the Ice-Cold Rules of Thermodynamics

The story of modern LNG wonders begins with a simple but profound question: how do we turn the feeling of “cold” into a scientific reality? The answer lies in the groundbreaking work of pioneers like James Joule and Sadi Carnot, whose discoveries in thermodynamics set the stage for every icy milestone that followed.

Joule’s Two-Way Street: Work and Heat Are Interchangeable

James Prescott Joule, a meticulous experimenter, proved that energy is never lost—only transformed. By stirring water and measuring the resulting temperature rise, Joule showed that work (like turning a paddle) and heat are two sides of the same coin. This breakthrough, known as the mechanical equivalent of heat, gave scientists a precise “energy ledger.” Now, they could calculate exactly how much work was needed to cool something down—a crucial step for anyone chasing lower and lower temperatures.

Carnot & Clausius: Nature Demands a Strategy

But Joule’s ledger was just the beginning. Sadi Carnot, often called the father of thermodynamics, asked a deeper question: how efficiently can we turn energy into cold? His analysis of ideal heat engines revealed a key rule: the bigger the temperature gap between your hot and cold reservoirs, the better your efficiency. In Carnot’s words:

“The production of cold requires work, and the colder the goal, the more cleverness needed.”

Rudolf Clausius took Carnot’s ideas further, formalizing the second law of thermodynamics. He introduced the concept of entropy—a measure of disorder—and declared that heat can’t just flow from cold to hot without help. This law set a hard boundary: you can’t simply will something to be colder; you need a smart, step-by-step approach.

Quick Tangent: Entropy with a Deck of Cards

Imagine a brand-new deck of cards—perfectly ordered. Shuffle it, and the order disappears. That’s entropy: the natural tendency for things to get more disordered. In cooling, entropy means you can’t just “unshuffle” the heat out of a system without putting in work.

Why We Need a Multi-Step Approach to Extreme Cold

These scientific advancements in thermodynamics and entropy explain why reaching truly frigid temperatures—like those seen in LNG plants (273 K, 200 K, 150 K, 112 K)—isn’t a one-step process. Each stage of cooling must be carefully planned, using clever engineering to move heat from one place to another, always respecting nature’s rules.

First Law: Energy is conserved—no magic shortcuts.

Second Law: No spontaneous heat flow from cold to hot (Clausius).

Carnot’s Principle: Efficiency rises with greater temperature differences.

From Joule’s energy accounting to Carnot’s efficiency map and Clausius’s entropy rules, the journey from equations to energy has been a relay of insight and ingenuity—each step bringing us closer to mastering the ice-cold frontiers of LNG technology.

Blueprints and Beer: Linde, Pictet, and the Engineering of Extreme Cold

The story of modern liquefied natural gas (LNG) plants—where digital screens flash temperatures like 273 K, 150 K, and 112 K—begins not in high-tech control rooms, but in the inventive workshops of 19th-century Europe. Here, a thirst for both scientific progress and cold beer sparked a revolution in cooling technology, led by visionaries like Carl von Linde and Raoul Pictet.

Linde’s Vapor-Compression: Putting Beer (and Science) on Ice

Carl von Linde was a German engineer with a practical problem: how to keep beer cold and fresh for longer. In 1876, he introduced the vapor-compression cycle, a process that used mechanical work to compress and expand gases, absorbing heat and producing cold. This wasn’t just a win for breweries—Linde’s invention became the backbone of industrial refrigeration, laying the groundwork for the Linde process and the cryogenic heat exchangers that would one day chill LNG.

Imagine the first taste of beer cooled by Linde’s machine—crisp, refreshing, and a testament to the power of applied science. As Linde himself might have said,

'With cold, as with beer, patience and process shape the outcome.'

Supercharged Cooling: The Cascade Cycle and Teamwork

But chilling beer was just the beginning. The next challenge was to liquefy gases once thought “permanent”—like oxygen and nitrogen. Enter the cascade cycle, a clever method pioneered by Pictet and Cailletet in 1877. Instead of trying to cool everything at once, they used a series of refrigerants, each colder than the last, to step down the temperature in stages. This teamwork approach—now called the cascade process—became the secret sauce for reaching ultra-low temperatures.

In a cascade cycle, one refrigerant (like propane) cools another (like ethylene), which in turn cools a third (like methane). This principle, later refined by Phillips Petroleum in the 1960s, is at the heart of every modern LNG plant. Today’s cryogenic heat exchangers—massive, coiled structures—still rely on Linde’s counter-current heat exchange, where outgoing cold gas pre-cools incoming warm gas, maximizing efficiency.

The Arms Race for Liquefying Permanent Gases

The late 1800s saw an “arms race” among scientists to liquefy the toughest gases. In 1877, both Pictet and Cailletet independently succeeded in liquefying oxygen using staged, cascade refrigeration. Their breakthroughs proved that with enough patience, process, and engineering, even the most stubborn molecules could be tamed.

These early innovations—Linde’s vapor-compression, the cascade process of Pictet and Cailletet, and the birth of cryogenic heat exchangers—form the blueprints for today’s LNG wonders. Each frosty milestone, from the first chilled beer to the modern LNG plant, is a testament to the relentless human pursuit of cold.

Pushing into the Impossible: Kamerlingh Onnes and the Helium Frontier

The race to the coldest temperatures took a dramatic leap in the early 20th century, when Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes set his sights on the last unconquered frontier: helium liquefaction. For decades, helium was considered a “permanent gas”—impossible to liquefy by any known means. But Onnes, guided by his relentless motto, “Door meten tot weten” (“Knowledge by measurement”), refused to accept the impossible.

Obsessive Precision: “Knowledge by Measurement”

Onnes’s laboratory in Leiden became a temple to precision. Every experiment was meticulously planned, every measurement double-checked. He understood that at the edge of physical possibility, even the smallest error could mean failure. His team’s obsession with accuracy set a new standard for scientific advancements in cryogenic recovery.

Dewar Flasks, Staged Cooling, and the 4.2 K Barrier

To reach helium’s liquefaction point—an astonishing 4.2 K above absolute zero—Onnes employed a series of ingenious techniques:

Staged Cooling: First, air was cooled and liquefied, then used to cool hydrogen, which in turn cooled helium. This stepwise approach was essential, as no single process could bridge the temperature gap.

Dewar Flask: The double-walled, vacuum-insulated Dewar flask (invented by James Dewar) was critical. It minimized heat leaks, allowing precious cold to be preserved long enough for helium to condense.

On July 10, 1908, after years of setbacks and near-misses, the impossible happened. The first drops of liquid helium formed and dripped into a waiting beaker. The laboratory erupted in celebration—cheers, handshakes, and even tears of joy. For Onnes and his team, it was the ultimate reward for their dedication to measurement and method.

“Knowledge by measurement.” – Heike Kamerlingh Onnes

Unlocking New Realms: Superconductivity and Beyond

The liquefaction of helium was more than a technical triumph—it opened the door to entirely new physics. In 1911, while studying metals cooled by liquid helium, Onnes discovered superconductivity: the complete disappearance of electrical resistance at ultra-low temperatures. This breakthrough would eventually revolutionize everything from MRI machines to quantum computing.

Onnes’s work also laid the groundwork for helium extraction and industrial helium liquefaction. During World War I, the first large-scale liquefaction of natural gas in the U.S. was driven by the need to extract helium for British dirigibles. Today, helium remains vital for scientific research, medical imaging, and space exploration.

The Legacy of the Helium Frontier

Kamerlingh Onnes’s relentless pursuit of the impossible—powered by precision, innovation, and the courage to measure the unknown—pushed humanity to the edge of absolute zero. His legacy lives on in every modern cryogenic recovery process and in the control rooms of LNG plants, where temperatures once thought unreachable are now routine data points on a screen.

From Lab Triumph to Industry Giant: How Cold Conquered Global Energy

The story of liquefied natural gas (LNG) technology is a tale of relentless human curiosity, scientific breakthroughs, and engineering marvels. What began as a quest to measure and master the sensation of cold has evolved into the backbone of a global energy industry, with LNG facilities now dotting coastlines and fueling economies worldwide.

The leap from laboratory experiments to industrial giants started with Georges Claude’s revolutionary turbo-expander. By extracting mechanical work as gases expanded and cooled, Claude’s invention dramatically improved the efficiency of industrial gas liquefaction. This innovation turned the dream of large-scale production of liquid oxygen, nitrogen, and eventually natural gas into a practical reality. The turbo-expander’s principle—extracting work from cold—remains at the heart of today’s LNG plants.

The next breakthrough came with the development of the cascade process and advanced heat exchangers. Engineers like Carl von Linde and later, the teams at ConocoPhillips and Air Products, built on Claude’s foundation. The Optimized Cascade Process, first applied commercially at Alaska’s Kenai LNG plant in 1969, used multiple refrigerants—propane, ethylene, and methane—in sequential cooling stages. This approach, along with propane precooled mixed refrigerant cycles (C3-MR), now powers over 80% of global LNG plants. These systems squeeze out every bit of cold, allowing natural gas to be chilled to around 112 K, shrinking its volume by about 600 times and making global shipment possible.

Step into a modern LNG facility or regasification plant, and you’ll see control screens glowing with numbers: 273 K, 200 K, 150 K, 112 K. To an outsider, these might seem like mere technical details. But each digit is a monument to scientific achievement—a direct descendant of Lord Kelvin’s absolute scale, Joule’s energy calculations, and the thermodynamic laws of Carnot and Clausius. These numbers are the language of cold, spoken fluently by every LNG operator and engineer, and they tell the story of a century-long relay from the laboratory to the world’s energy hubs.

Today, LNG export is a global enterprise. Mega-trains built by Technip, JGC, and Chiyoda, massive coil-wound heat exchangers, and fleets of LNG carriers connect gas fields to homes and industries across continents. Offshore liquefaction and regasification plants push the boundaries even further, making LNG accessible where pipelines cannot reach. The Kenai LNG plant’s pioneering spirit lives on in every new facility, as the industry continues to grow in scale, efficiency, and reach.

In the end, the conquest of cold is more than a technical triumph—it is a testament to human ingenuity. As one expert put it,

Cold has become not a curiosity, but a pillar of the world economy.

The glowing digits in every LNG control room are not just numbers; they are the living legacy of a journey from scientific wonder to industrial might.

TL;DR: From the earliest chills to LNG mega-facilities, relentless curiosity and collaboration have turned cold into a force that shapes our world. The saga continues with every frosty breakthrough and hum of control-room data.

Comments

Post a Comment