Chilling Out: How Cryogenic Science and Thermodynamics Transformed Industry (And Why Students Should Care)

Few things are as memorable as the first time you accidentally stuck your tongue to something frozen, learning the hard way that 'cold' can be more dangerous (and fascinating) than you thought. Imagine scientists in the 19th century doing the intellectual equivalent—wondering how to trap, measure, and eventually wield cold. This isn’t just about weather. It’s a story of how world-changing innovations—like the shiny digital readouts in modern gas plants—started from basic curiosity and some very clever problem-solving.

From Guesswork to Numbers: The Birth of Temperature Measurement

Before the rise of cryogenics science and technology, humanity’s understanding of temperature was rooted in sensation. People described the cold with phrases like, “It’s freezing!” or “It feels chilly,” relying entirely on subjective experience. This approach, while relatable, left science and industry without a reliable way to compare or control temperature—especially as the pursuit of extreme cold became essential for progress in physics, chemistry, and engineering.

The turning point arrived in the 17th century with the invention of the thermometer. This simple yet revolutionary tool allowed temperature to be expressed as a number, not just a feeling. Suddenly, “cold” and “hot” could be measured, compared, and reproduced—laying the groundwork for the precision required in modern cryogenics science and technology.

Three Scales That Changed Everything

As thermometers became more common, scientists realized the need for standardized temperature scales. Three major systems emerged, each with its own logic and legacy:

Fahrenheit Scale (18th century): Developed by Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit, this scale set its zero point at the coldest mixture he could create (saltwater ice), with 32°F as water’s freezing point and 96°F originally representing human body temperature. It became popular in English-speaking countries for everyday use.

Celsius Scale (18th century): Anders Celsius proposed a scale based on water’s behavior—0°C for freezing, 100°C for boiling. This logical, decimal-based system quickly became the scientific standard in most of the world.

Kelvin Scale (1848): William Thomson, later Lord Kelvin, introduced a scale anchored not to water, but to the fundamental limits of nature. Zero Kelvin (0 K) marks absolute zero, the lowest possible temperature where all molecular motion stops. The Kelvin scale is essential for cryogenics, as it provides a universal, material-independent reference for measuring and controlling extreme cold.

Milestone | Century | Key Value |

|---|---|---|

Thermometer Invented | 17th | First objective measurement |

Fahrenheit Scale | 18th | 0°F (saltwater ice), 32°F (water freezes) |

Celsius Scale | 18th | 0°C (freezing), 100°C (boiling) |

Kelvin Scale | 1848 | 0 K = -273.15°C (absolute zero) |

Kelvin’s Legacy: Measuring the Limits

Lord Kelvin’s approach—“measure everything objectively”—transformed how scientists explored the coldest realms. His famous words still guide research today:

“When you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it.” – William Thomson (Lord Kelvin)

By establishing the Kelvin scale and the concept of absolute zero, Kelvin gave cryogenics science and technology a foundation for innovation. Today, digital displays in LNG plants and research labs show temperatures like 273 K, 150 K, or even 4.2 K—numbers that would be meaningless without this historic journey from guesswork to measurement. The Kelvin scale and absolute zero remain fundamental to understanding and controlling the extreme cold at the heart of cryogenics.

Getting Technical: Thermodynamics, Cooling Cycles & The Road to Extreme Cold

Behind every cryogenic breakthrough lies the rigorous application of thermodynamics laws and ingenious engineering. Understanding how we reach extreme cold starts with two fundamental principles: the First and Second Laws of Thermodynamics. These laws not only explain why cooling is possible but also set the boundaries for what’s achievable in cryogenic science and industry.

Thermodynamics Laws Applications: The Rules of Cold

The First Law of Thermodynamics—often summed up as “you never get cold for free”—states that energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transferred or transformed. In mathematical terms, ΔU = Q - W, where ΔU is the change in internal energy, Q is heat added, and W is work done by the system. Every time an LNG plant chills natural gas, it’s not making energy disappear; it’s moving heat from one place to another, using compressors and expanders to shuffle energy around.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics tells us that heat naturally flows from hot to cold. To reverse this—cooling something below its surroundings—requires external work. Carnot’s equation, η = 1 - Tc/Th, defines the theoretical efficiency limit, where Tc and Th are the cold and hot reservoir temperatures. As James Prescott Joule famously said:

“The fundamental laws of thermodynamics will never be overthrown.”

Vapor-Compression Refrigeration Cycle: Turning Equations into Machines

Engineers like Carl von Linde transformed theory into practice with the vapor-compression refrigeration cycle. This process compresses a refrigerant gas, cools it, and then allows it to expand. The expansion absorbs heat, dropping the temperature dramatically. A teacher once likened it to squeezing a balloon (compression), letting it cool, then popping it—feeling the chill as the gas expands. That’s the Joule-Thomson Effect Cryogenics in action: most gases cool when they expand from high to low pressure, a principle discovered in the mid-1800s and still central to cryogenic cooling.

Cascade Refrigeration Systems: The Cool Baton Relay

Reaching ultra-low temperatures isn’t possible with a single refrigerant. Cascade refrigeration systems solve this by using a series of refrigerants, each with a lower boiling point. It’s like handing off a “cool baton” from one stage to the next, each time getting colder. This approach, pioneered by Raoul Pictet and Louis Cailletet, allows LNG plants and research labs to achieve temperatures far below what a single-stage system could reach. Modern LNG facilities use multi-stage cascades—propane for pre-cooling, ethylene or mixed refrigerants for deeper chilling, and methane for the final plunge to -161.5°C.

First Law: Energy is shuffled, not lost (

ΔU = Q - W).Second Law: Cooling always needs work; efficiency is limited (

η = 1 - Tc/Th).Vapor-Compression: Compress, cool, expand—repeat.

Joule-Thomson Effect: Gases chill as they expand.

Cascade Systems: Multi-stage cooling for extreme cold.

These principles and cycles are the backbone of cryogenic technology, enabling everything from LNG production to the discovery of superconductivity. Mastering them is essential for anyone interested in the science and engineering of extreme cold.

The Leap to Industry: Cryogenic Engineering in Action (and the Surprising Superpowers Unlocked)

Cryogenic Engineering Innovations have transformed the industrial world, with Liquefied Natural Gas Temperature Control standing as one of the most dramatic examples. To safely store and transport natural gas, engineers must cool methane to a staggering 111.7 K (-161.5°C). This process shrinks its volume by more than 600 times—a true “shrinkage miracle”—making global LNG trade possible.

The Coolness Relay: From Scientific Curiosity to Industrial Powerhouse

The journey to this achievement reads like a relay race in scientific ingenuity. Each breakthrough handed the baton to the next, unlocking new “superpowers” for industry:

Dewar’s Vacuum Flask: Provided the essential insulation for storing ultra-cold liquids.

Kamerlingh Onnes’s Helium Liquefaction (1908): Achieved 4.2 K, opening the door to extreme cryogenics.

Claude’s Work-Recovery Turbines: Used expanding gases to do work, boosting efficiency and making large-scale liquefaction feasible.

Modern LNG plants are the ultimate expression of these innovations. Their core mission: cool methane using multi-stage cascade refrigeration—a process where each refrigerant (propane, ethylene, methane) takes the gas a step closer to liquefaction. This “ladder of cooling” is the foundation of Modern LNG Processes Efficiency.

How the Modern LNG Plant Works

Pre-cooling with propane removes most of the heat.

Main cooling uses ethylene and methane, following the cascade principle.

Sub-cooling relies on turbo-expanders and the Joule-Thomson effect to reach storage temperature.

Digital controls monitor every stage, with screens displaying 273 K, 200 K, 150 K, and 112 K—ensuring safety and efficiency.

The ConocoPhillips Optimised Cascade Technology and Air Products AP-C3MR/AP-DMR Systems are industry leaders, combining cascade and mixed-refrigerant cycles for maximum efficiency. These systems embody the best of cryogenic freezing technology, using energy recovery and precise controls to minimize waste and cost.

“Our progress in liquefying gases rewrote what was possible in science and industry.”

– Heike Kamerlingh Onnes

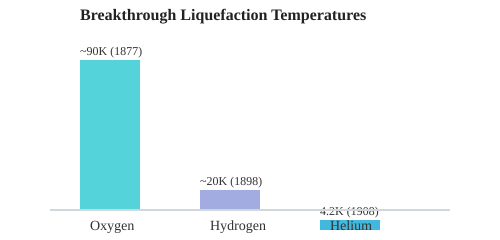

Breakthroughs in Cryogenic Freezing Technology: A Comparative Table

Substance | Liquefaction Temp (K) | Year | Key Figure(s) | Technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Oxygen | ~90 | 1877 | Cailletet, Pictet | Joule-Thomson, Cascade |

Hydrogen | ~20 | 1898 | James Dewar | Dewar Flask, Cascade |

Helium | 4.2 | 1908 | Kamerlingh Onnes | Cascade, Turbo-Expander |

SVG Chart: Breakthrough Liquefaction Temperatures

These landmark achievements—each a rung on the “coolness ladder”—are the backbone of today’s cryogenic freezing technology and LNG industry. From the first vacuum flasks to the ultra-efficient AP-C3MR systems, the relay of innovation continues, unlocking new industrial superpowers with every generation.

Odd Tangent: Why Your Future Might Depend on Mastering the Cold

Cryogenics is far more than a niche branch of physics—it is the invisible engine powering some of the most transformative technologies of our era. While the control of extreme cold is most visible in the vast LNG terminals liquefying natural gas for global energy markets, its true reach extends into fields that shape daily life and the frontiers of science. From superconducting magnets in MRI machines to quantum computing cryogenics, and from medical cryogenic applications to cryogenic cooling technologies for sustainable energy sources, the mastery of low temperatures is rapidly becoming a foundation for modern innovation.

Consider the impact of superconductivity, discovered at just 4.2 K by Heike Kamerlingh Onnes in 1911. This phenomenon—where electrical resistance vanishes—now underpins the powerful magnets found in MRI scanners, enabling non-invasive diagnostics that save countless lives. These superconducting MRI magnets rely on liquid helium cooling to maintain their ultra-cold state, a direct application of cryogenic engineering. As Onnes famously remarked,

“When you’re this close to absolute zero, the possibilities for discovery are endless.”

The same principles drive the quantum revolution. Quantum computing cryogenics cools delicate qubits to fractions of a degree above absolute zero, where quantum effects can be controlled and harnessed. Without advanced cryogenic cooling technologies, the dream of quantum computers—capable of solving problems in seconds that would take classical computers millennia—would remain out of reach. This is not science fiction; it is the foundation of a new era in computing, cybersecurity, and artificial intelligence.

Medicine, too, is being transformed by the cold. Medical cryogenic applications now include the long-term storage of genetic material, stem cells, and even entire organs at temperatures below -150°C. This enables breakthroughs in gene therapy, regenerative medicine, and fertility preservation. The ability to store and transport biological samples safely and reliably is a direct result of advances in cryogenic science.

Looking forward, cryogenics is set to play a pivotal role in the transition to sustainable energy sources. The production, storage, and transportation of green hydrogen—a key player in the future energy mix—depend on efficient cryogenic cooling technologies. Likewise, space exploration, next-generation electronics, and even food preservation are all being reshaped by our ability to tame the cold.

For today’s students, this means that the science learned in the classroom is not just academic—it is the groundwork for tomorrow’s breakthroughs. Imagine a world where cryogenic engineers are as sought-after as software developers, because the ability to control the cold unlocks everything from medical miracles to green energy solutions. The question is not whether you will encounter cryogenics in your future, but whether you will be a consumer or a creator in this new cold-powered world.

In mastering the cold, we are not just pushing the boundaries of temperature—we are pushing the boundaries of what is possible. The next era of discovery, innovation, and sustainable progress will belong to those who understand and harness the science of cryogenics.

TL;DR: Cryogenics isn’t just for mad scientists or sci-fi movies—it's the disciplined, rule-bound art of harnessing extreme cold, grounded in centuries of basic physics, and now central to industries from energy to medicine. Understanding its backbone—the Kelvin scale, thermodynamic laws, and cooling cycles—opens doors to real-world tech and future careers.

Comments

Post a Comment