The sharp sting of an ice-cold hand always jolted me awake during winter childhoods—and even today, I find myself pondering: what is cold, really? Is it just a bone-deep feeling, or something more? This is the story of humanity’s relentless pursuit to measure, create, and finally master cold, a journey filled with unlikely heroes, accidental genius, and moments of stunning breakthrough.

1. From Aristotle to Fahrenheit: Cold as a Concept and Measurement Quest

For much of human history, the concept of cold was more a matter of philosophy than science. Ancient thinkers, most notably Aristotle, classified cold as one of the four fundamental elements—alongside earth, air, fire, and water. In this worldview, cold was not a quantity to be measured but a basic quality of the natural world, experienced subjectively and described through sensation. The journey from this abstract understanding to the precise science of temperature measurement marks a pivotal chapter in the cryogenics history timeline and the broader evolution of low-temperature technology.

Philosophy to Physics: Cold as a Puzzling Sensation

For centuries, cold remained a philosophical puzzle. People described it in relative terms—colder or warmer—but lacked any way to quantify or compare their experiences. This limitation meant that scientific collaboration and experimentation across distances were nearly impossible, as there was no common language or standard for describing temperature. The need for objective measurement became clear as natural philosophers sought to understand the world in more precise terms.

Galileo’s Thermoscope: The First Step Toward Measurement (1592)

A major breakthrough came in 1592 with Galileo Galilei’s invention of the thermoscope. This early device demonstrated that air expanded and contracted with changes in temperature, causing a column of water to rise or fall. However, Galileo’s thermoscope lacked a numerical scale, so while it could show that one object was hotter or colder than another, it could not provide standardized readings. As a result, scientists in different locations could not compare their results—a significant barrier to the advancement of temperature measurement advances.

Fahrenheit’s Standardized Thermometer: A Revolution in Science (1724)

The next leap forward came in 1724, when Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit introduced the first reliable, standardized thermometer. By using mercury, which expands and contracts uniformly, and by establishing fixed reference points—0°F for a salt-ice mixture, 32°F for the freezing point of water, and approximately 96°F for human body temperature—Fahrenheit made it possible to compare temperatures accurately across different places and experiments. This innovation marked the true beginning of global scientific collaboration in temperature studies. As historian Hasok Chang noted:

"The thermometer was not just an instrument, but a revolution in understanding."

With Fahrenheit’s scale, temperature became a measurable, reproducible quantity, transforming cold from a subjective feeling into an objective fact.

Celsius and Linnaeus: The Blueprint for Global Science (1742)

Building on Fahrenheit’s work, Anders Celsius introduced the centigrade scale in 1742. Originally, Celsius set 0°C as the boiling point of water and 100°C as its freezing point—an inversion of today’s convention. Shortly after, Carl Linnaeus reversed the scale to its modern form: 0°C for freezing and 100°C for boiling. This 100-degree span made the scale intuitive and easy to use, quickly becoming the blueprint for scientific research worldwide. The centigrade (now Celsius) scale’s adoption allowed scientists everywhere to communicate and compare results with unprecedented precision, accelerating the pace of discovery in the low-temperature technology timeline.

Standardization: The Foundation of Cryogenics History Timelines

The development and standardization of temperature measurement tools—beginning with Galileo’s thermoscope, advancing through Fahrenheit’s mercury thermometer, and culminating in the Celsius scale—transformed the study of cold. These advances laid the groundwork for the emergence of cryogenics as a scientific discipline and enabled the systematic exploration of ever-lower temperatures. The ability to measure cold accurately was not just a technical achievement; it was the essential first step in turning cold from a philosophical curiosity into a cornerstone of modern science.

2. The Great Heat Debate: Caloric Theory vs. Energy and Thermodynamics

The evolution of cryogenics history timelines is closely tied to a fundamental debate about the nature of heat. In the early days of low-temperature technology, scientists struggled to define what they were actually measuring with their new thermometers. Was heat a material substance, or something else entirely? This question shaped the direction of scientific discovery for over a century and laid the groundwork for breakthroughs by pioneers like Heike Kamerlingh Onnes.

The Caloric Theory: Heat as a Mysterious Fluid

For much of the 18th and early 19th centuries, the caloric theory dominated scientific thinking. According to this idea, heat was a weightless, invisible fluid called "caloric" that flowed from hotter objects to colder ones. The theory seemed to explain everyday experiences—such as the sensation of warmth or the melting of ice—but it was based on the assumption that caloric was a conserved substance, much like water or air.

However, as temperature measurement became more precise, inconsistencies began to emerge. The most notable challenge came from Benjamin Thompson, better known as Count Rumford. In the late 18th century, Rumford observed that boring cannons at a Munich arsenal produced seemingly endless amounts of heat, far more than could be explained by the loss of any material substance. He concluded that heat could not be a fluid, but must be related to motion or energy.

- Late 18th Century: Rumford’s cannon boring experiments cast doubt on caloric theory.

- 1760s–1800s: Growing evidence that heat was not a material fluid.

Joule’s Experiments: Heat as Energy

The decisive blow to caloric theory came from James Prescott Joule in the 1840s. Joule’s famous paddle-wheel experiments demonstrated that mechanical work could be converted directly into heat. By stirring water with a falling weight, he showed that the temperature of the water increased in proportion to the work done. This proved that heat was not a substance, but a form of energy.

"Energy is neither created nor destroyed—it merely changes form." – James Prescott Joule

Joule’s findings led directly to the First Law of Thermodynamics, the principle of energy conservation. This law became foundational for all later developments in cryogenics and low-temperature technology, as it revealed that heat, work, and energy were interchangeable and measurable quantities.

- 1840s: Joule’s paddle-wheel experiments establish heat as energy.

- First Law of Thermodynamics: Energy conservation principle emerges.

The Birth of Thermodynamics: Carnot, Clausius, and Kelvin

With the realization that heat was energy, scientists turned to understanding how it moved and changed. In 1824, Sadi Carnot published his analysis of ideal heat engines, showing that their efficiency depended only on the temperature difference between heat sources, not on the materials used. This insight was crucial for the development of refrigeration and engines, both key elements in the low-temperature technology timeline.

Building on Carnot’s work, Rudolf Clausius and William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) formalized the laws of thermodynamics. Clausius introduced the concept of entropy, describing the direction and irreversibility of natural processes. Kelvin, in 1848, proposed the absolute temperature scale, anchored at Absolute Zero (−273.15°C), the theoretical point where all classical molecular motion ceases.

- 1824: Carnot’s book on heat engines published.

- 1848: Kelvin introduces the absolute temperature scale.

- Clausius: Establishes the Second Law of Thermodynamics and entropy.

These breakthroughs redefined the scientific understanding of heat and cold, transforming them from abstract sensations into measurable, controllable forms of energy. This new framework was essential for the later achievements of Heike Kamerlingh Onnes and others, who pushed the boundaries of cold to new extremes in the quest to reach Absolute Zero.

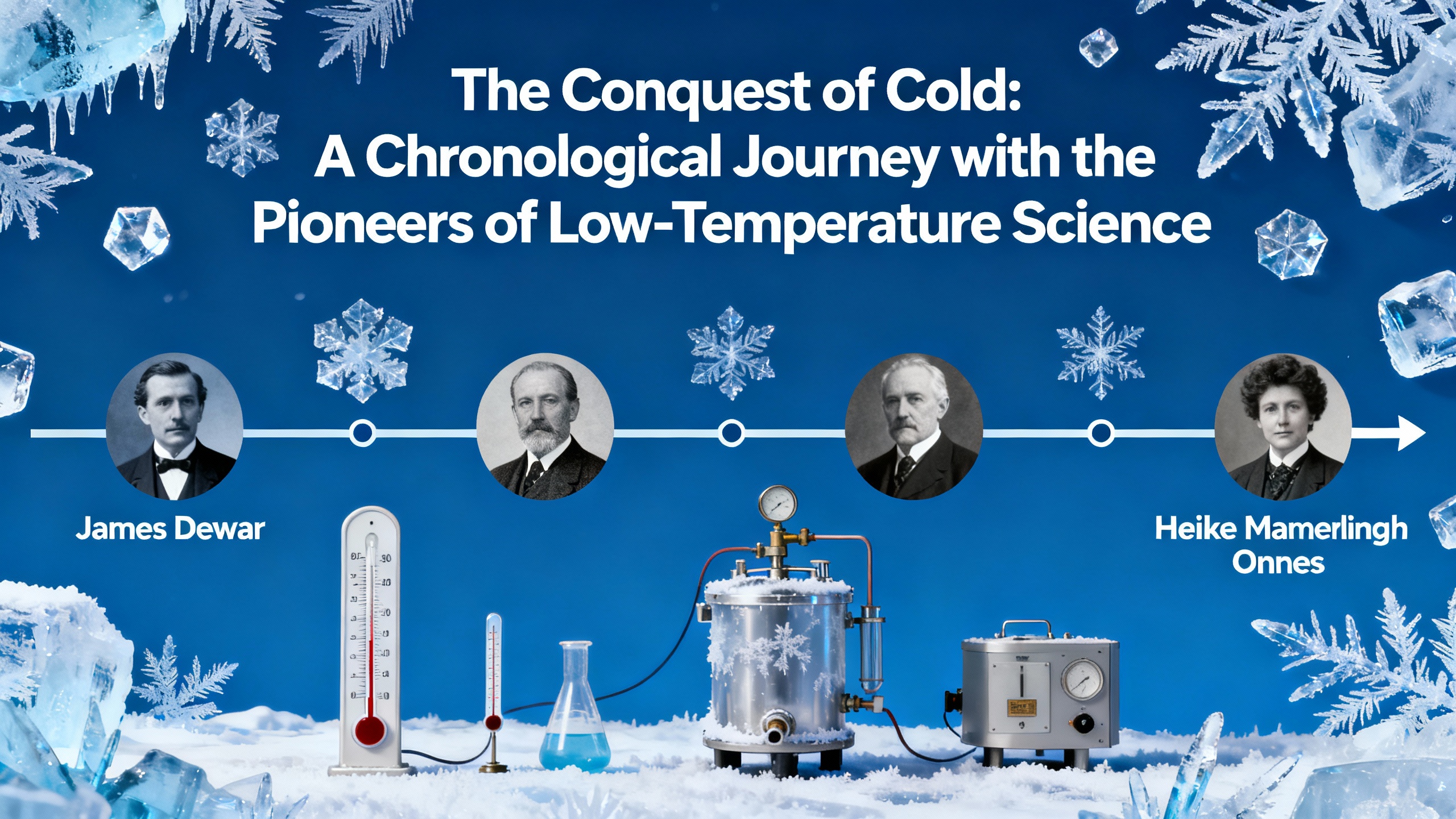

3. Racing to Absolute Zero: The Era of Experimental Cold

The journey to understand and control cold entered a new era in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—a period often called the “race to absolute zero.” This era was defined by a series of remarkable breakthroughs in the liquefaction of gases, each milestone pushing the boundaries of what was thought possible and laying the foundation for modern cryogenics. The Cryogenics history timelines are marked by the work of pioneering scientists who transformed cold from a mysterious sensation into a measurable and manipulable scientific frontier.

Michael Faraday: Challenging the Immutable (1820s)

In the 1820s, Michael Faraday made a pivotal contribution to the low-temperature technology timeline by successfully liquefying gases such as chlorine and sulfur dioxide. Before Faraday, many believed that certain “permanent gases” could never be condensed into liquids. Faraday’s experiments proved otherwise, shifting scientific thinking about the states of matter and demonstrating that all gases could, in principle, be transformed by lowering temperature and increasing pressure. This breakthrough was a crucial step in the development of cryogenics as a science.

Louis Cailletet & Raoul Pictet: Breaking Old Boundaries (1877)

The next major leap came in 1877, when Louis Cailletet in France and Raoul Pictet in Switzerland independently achieved the liquefaction of oxygen. Using different techniques—Cailletet with rapid expansion and Pictet with a cascade of cooling agents—they both managed to create fleeting drops of liquid oxygen. This achievement shattered the belief that some gases were fundamentally unliquefiable, and it marked a turning point in the cryogenics history timelines. The success of Cailletet and Pictet inspired a new generation of scientists to pursue even lower temperatures.

James Dewar: Hydrogen and the Vacuum Flask (1898)

By the end of the nineteenth century, James Dewar had taken up the challenge of liquefying hydrogen, a gas with an even lower boiling point than oxygen. In 1898, Dewar succeeded, reaching temperatures below -252°C. To store these extremely cold liquids, he invented the vacuum flask, a double-walled container with a vacuum between the layers to minimize heat transfer. This innovation, now known as the Thermos, remains a staple in laboratories and daily life. Dewar’s work not only advanced the low-temperature technology timeline but also provided essential tools for future experiments.

Heike Kamerlingh Onnes: Helium Liquefaction and Superconductivity (1908–1911)

The quest for the coldest temperatures reached its zenith in 1908, when Heike Kamerlingh Onnes at the University of Leiden became the first to liquefy helium. Achieving temperatures below 4.2 K (-269°C), Onnes opened the door to a new realm of physics. In 1911, while studying metals at these ultra-low temperatures, he discovered superconductivity—a phenomenon where electrical resistance drops to zero. This finding, made possible by helium liquefaction, marked a turning point in both cryogenics and quantum mechanics. As Onnes famously reflected:

"Reaching ever lower temperatures felt like magic, but it was merely mastery of nature’s laws."

Legacy and Impact

The relentless pursuit of absolute zero by Faraday, Cailletet, Pictet, Dewar, and Onnes not only advanced the cryogenics history timelines but also enabled fundamental discoveries in physics and technology. Their breakthroughs in helium liquefaction and superconductivity continue to shape modern science, from MRI machines to quantum computing. The race to absolute zero remains a testament to human curiosity and ingenuity, with each milestone building on the last to reveal new wonders at the coldest frontiers of nature.

4. Cold Goes Big: From Laboratory Curiosity to Industrial Titan

The journey of cold from a laboratory curiosity to a driving force of modern industry is a story of invention, ambition, and societal transformation. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw cold move out of the hands of scientists and into the fabric of everyday life, thanks to breakthroughs in refrigeration systems history and the vision of pioneers like Carl von Linde, Georges Claude, and Willis Carrier.

Carl von Linde and the Vapor-Compression Refrigeration System

In 1895, Carl von Linde revolutionized the world with the development of the vapor-compression refrigeration system. This technology enabled the commercial-scale production of liquefied gases, marking a turning point in the industrialization of cold. Linde’s system used a closed cycle where a refrigerant is compressed, condensed, expanded, and evaporated, absorbing heat from its surroundings and producing cooling. This innovation did not just make cold measurable—it made it a commodity.

Linde’s refrigeration systems history is closely tied to the rise of new industries. For the first time, it became possible to separate and store industrial gases like oxygen and nitrogen on a large scale. This capability fueled the growth of the chemical, metallurgical, and medical sectors. As Linde himself famously stated:

"Cold built the modern city—refrigeration, skyscrapers, and global commerce owe much to it."

Georges Claude and the Turbo-Expander

Building on Linde’s foundation, Georges Claude introduced the turbo-expander in the early 1900s. This device extracted mechanical work from expanding gases, dramatically increasing the efficiency of large-scale cooling and air separation. Claude’s innovation allowed for even greater output and lower costs in the production of industrial gases, powering the rise of companies like Air Liquide and setting the engineering standards for modern cryogenic systems.

- Turbo-expander technology: Enhanced cooling efficiency and output

- Industrial gases sector: Enabled economic production and distribution of oxygen, nitrogen, and argon

- Modern cryogenics: Laid the groundwork for advanced cooling in science and industry

Refrigeration Systems: Transforming Food, Medicine, and Cities

The industrialization of cold had profound practical impacts. Refrigeration systems made it possible to preserve food over long distances and periods, reducing spoilage and enabling global trade. Hospitals and laboratories could now store vaccines, blood, and other vital medical supplies safely. The ability to control temperature also spurred the growth of cities, allowing for denser populations and the construction of skyscrapers, which relied on mechanical cooling for comfort and safety.

Refrigeration moved from being an exotic laboratory experiment to a part of daily existence, reshaping society and the economy. Cold became a silent partner in the rise of modern life, supporting everything from grocery stores to data centers.

Willis Carrier and the Invention of Modern Air Conditioning

In 1906, Willis Carrier patented the first modern air conditioning system. His invention went beyond simple cooling; it controlled humidity and air quality, forever changing the workplace and domestic life. Factories could now operate year-round, regardless of weather, improving productivity and worker comfort. Homes, offices, and public spaces became more livable, especially in hot climates, influencing architecture and urban planning.

- Workplace transformation: Enabled year-round manufacturing and office work

- Domestic comfort: Made homes and public spaces more livable

- Architectural impact: Allowed for the design of larger, glass-enclosed buildings

The combined efforts of Linde, Claude, and Carrier turned cold into an industrial titan. Their innovations underpin the refrigeration and air conditioning systems that are now essential to food safety, healthcare, commerce, and the very structure of modern cities.

5. Beyond Freezing: Cold and the Maps of the Possible (Cryonics, Quantum Frontiers, and More)

As the mastery of cold advanced from philosophical musings to laboratory triumphs, a new era of possibility emerged—one where the boundaries of life, death, and the very fabric of matter could be questioned. The story of cold did not end with the liquefaction of helium or the discovery of superconductivity; instead, these breakthroughs set the stage for even more ambitious dreams. The practical uses of ultra-cold technology began to shape medicine, physics, and even the hopes of those seeking to transcend mortality itself.

The modern cryonics movement traces its roots to 1962, when Robert Ettinger published The Prospect of Immortality. In this book, Ettinger boldly proposed that people could be preserved at ultra-low temperatures after death, with the hope that future science might one day revive them. His idea—“freeze now, revive later”—sparked both fascination and fierce debate. As Ettinger himself wrote,

“Cryonics is not so much science fiction as an act of scientific faith.”The term “cryonics” was coined just a few years later, in 1965, marking the beginning of a movement that would challenge the definitions of life and death.

The first real test of cryonics came in 1967, when Dr. James Bedford, a psychology professor, volunteered to become the world’s first frozen patient. His body was cooled and stored in liquid nitrogen, and he remains preserved to this day. The outcome of Bedford’s preservation is still debated, and his case stands as a symbol of both hope and uncertainty in the cryonics history timelines. The movement quickly drew attention, but also encountered major setbacks. In 1979, the infamous Chatsworth crypt failure resulted in the loss of several cryonically preserved bodies, highlighting the technical and ethical challenges that continue to surround the field.

Despite these controversies, the cryonics movement and life extension efforts have persisted, fueled by advances in low-temperature science. The ability to reach and maintain temperatures near absolute zero, made possible by the liquefaction of helium and the development of reliable storage methods using liquid nitrogen, has not only kept the dream of cryonics alive but also revolutionized modern medicine. Today, the same technologies that preserve cryonics patients enable routine MRI scans, the long-term storage of biological samples, and the preservation of organs for transplantation.

The impact of cold extends far beyond medicine. The discovery of superconductivity—a phenomenon first observed by Heike Kamerlingh Onnes after he achieved helium liquefaction in 1908—opened the door to new realms of quantum physics. Superconductors, which conduct electricity without resistance at ultra-low temperatures, are now essential for powerful magnets in MRI machines and particle accelerators. Even more remarkably, the pursuit of lower and lower temperatures has led to the creation of Bose-Einstein condensates and the exploration of quantum computing, where matter behaves in ways that defy classical physics.

Today, researchers continue to push the boundaries, reaching temperatures in the millikelvin and even nanokelvin range. These extreme conditions allow scientists to study superfluidity, quantum entanglement, and other phenomena that may one day transform technology and our understanding of the universe. While cryonics remains controversial—its scientific plausibility and ethical implications still hotly debated—the technologies developed in the quest for cold have already changed the world.

In conclusion, the journey from the first thermometers to the frontiers of quantum physics reveals how the conquest of cold has mapped out new possibilities for science, technology, and even human destiny. As the pioneers of low-temperature science have shown, each step into the unknown brings not only new knowledge, but also new dreams—dreams that continue to inspire and challenge us in the ever-chilling search for what is possible.

TL;DR: Generations of curious minds turned the chill of winter from a mystery into a measurable and indispensable tool for science, industry, and medicine. Today, the race to reach even lower temperatures reveals secrets that could change the world as we know it.

Comments

Post a Comment