Let’s be honest: most people see a modern ship and marvel at its size or speed, not the mysterious magic that lets a giant propeller spin in the hull without springs of oil gushing into the sea. Years ago at a midnight port call, a chief engineer told me, 'If that stern tube lets go, you’d be ankle-deep in seawater before your coffee gets cold.' That mix of admiration and anxiety—for technology quietly doing its job—gave me an appreciation for ship systems most folks never think about. This post is a backstage pass to the stern tube: a tale of odd materials, creative genius, missteps, comeback stories, and the environmental forces shaping tomorrow’s vessels. Brace yourself for a look at the engineering backbone of the shipping world—and why its story is weirder, more important, and more colorful than you might expect.

A Window into the Propeller Shaft Hull Interface: Not Just a Hole in the Boat

When considering the marvels of marine engineering, it’s easy to focus on the visible giants—the hulls, decks, and towering superstructures. Yet, one of the most critical and ingenious engineering feats lies hidden below the waterline: the propeller shaft hull interface. This is not simply a hole in the boat; it is a carefully engineered gateway where the ship’s power meets the ocean, and where vulnerability and genius truly go hand in hand.

“In maritime engineering, the place where shaft meets hull is where vulnerability and genius go hand in hand.”

– Chief Engineer, Hank Larsen

From Bore Holes to Self-Lubricating Wood

Early ships solved the challenge of transmitting power to the propeller with remarkable simplicity. The propeller shaft passed through a basic bore hole in the stern frame—ingeniously simple, and surprisingly effective at keeping the sea at bay. The secret weapon? Lignum vitae, a dense, oily hardwood known as the “wood of life.” With a density up to 1.23 g/cm³, this wood actually sinks in water, and its natural oils provided self-lubrication. As the shaft rotated, seawater acted as both lubricant and coolant, making the earliest stern tube system engineering a model of self-sufficiency.

Lignum vitae: Naturally oily, dense, and self-lubricating

Seawater lubrication: Primitive but effective—when the sea was clean

The Achilles Heel: Sand and Silt

Despite its brilliance, this system had a major flaw: abrasive particles. Sand and silt, especially in shallow ports or muddy rivers, would grind down the wooden bearings, leading to increased wear and eventual failure. This vulnerability set the stage for future innovation as ships grew larger and faster, and as the demands on the propeller shaft hull interface intensified.

The Modern Interface: A Complex Engineering Ecosystem

Today’s stern tube is a far cry from its wooden ancestor. Now, it is a complex assembly of advanced materials and precision components, all designed to ensure reliability, efficiency, and environmental protection. A typical modern stern tube contains:

Bearings: Usually two—an aft (outboard) and a forward (inboard) bearing, supporting the shaft and absorbing loads

Seals: Multiple rings or mechanical face seals to keep lubricants in and seawater out

Tubular housing: A robust, welded structure integrated into the hull

Sensors: Monitoring temperature, vibration, and lubricant quality for predictive maintenance

Advanced materials: From white metal (Babbitt) alloys to composite polymers in water-lubricated systems

Precision Alignment: The Laser Advantage

One of the most challenging tasks in marine engineering terminology is aligning the propeller shaft with the hull. Modern shipbuilders use optical or laser alignment systems, achieving tolerances of less than 0.05 mm deviation. Even minor misalignment can cause excessive vibration, premature bearing wear, and catastrophic failures. Proper alignment is not just a technical detail—it is foundational to the vessel’s reliability and efficiency.

The evolution of the propeller shaft hull interface illustrates how marine engineering has transformed a simple hole in the boat into a sophisticated, multi-layered system—one that quietly underpins the safety, efficiency, and sustainability of global shipping.

From Oily Beginnings to Modern Marvels: The Oil vs Water Lubricated Bearings Saga

Modern ships are engineering giants, but the real magic often happens out of sight—deep within the stern tube, where the propeller shaft meets the hull. Here, the saga of oil vs water lubricated bearings has played out for over a century, shaping the reliability, efficiency, and environmental footprint of global shipping.

Industrial Revolution: From Wood to Babbitt Metal and Oil Lubrication

Early ships used lignum vitae, a naturally oily hardwood, for their water lubricated bearings. Seawater acted as both lubricant and coolant, and the system was simple and self-sustaining. However, as ships grew larger and faster during the industrial revolution, wooden bearings couldn’t withstand the increased loads and speeds. The breakthrough came with Babbitt metal—an alloy typically composed of ~89% tin, 7% antimony, and 4% copper—ushering in the era of oil lubricated bearings.

“The Babbitt metal bearing ushered in an era of oil-lubricated reliability, but never underestimate the ocean’s talent for finding leaks.” – Technical Lead, Sarah Yamada

Game-Changer: The Hydrodynamic Oil Film

The genius of oil lubrication lies in the hydrodynamic oil film. At speed, the shaft literally floats on a thin cushion of oil, virtually eliminating metal-on-metal contact. This reduces friction, minimizes wear, and extends bearing life—often 5 to 15 years with proper maintenance. Oil systems typically operate at a slight positive pressure (header tank ~0.5 bar above seawater) to keep water out and oil in. But this advancement brought a new challenge: containment. If seals fail, oil leaks can be catastrophic, both operationally and environmentally.

Anecdote: When Oil Fails

Consider the case of an engineer aboard a merchant vessel mid-Atlantic. Trusting in the “simple” reliability of oil, he was blindsided when a radial lip seal failed. Oil began seeping into the sea, triggering alarms and forcing an emergency shutdown. The ship limped to port, facing not only costly repairs but also a potential MARPOL fine of up to $25,000 per incident. This story underscores the critical importance—and vulnerability—of oil containment.

Water’s Comeback: Advanced Composites and the Green Equation

Today, environmental regulations and sustainability goals are driving a resurgence in water lubricated bearings. Modern systems use advanced composites—such as thermoset polymers pioneered by Thordon Bearings—offering robust performance with zero oil pollution risk. While these systems are inherently green and simplify fluid management, they can be sensitive to abrasive particles and may require enhanced filtration. The initial capital expenditure is typically 15–30% higher than conventional systems, but the environmental benefits are undeniable.

Comparing Bearing Technologies

Type | Performance | Pros | Cons | Environmental Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Water-Lubricated (Lignum Vitae/Composite) | Good (modern composites), moderate wear | Zero oil risk, simple system | Sensitive to abrasives, potential noise/vibration | Environmentally ideal |

Oil-Lubricated (Babbitt Metal) | Excellent, low wear | Low friction, long life | Risk of oil leaks, complex seals | Potential pollution risk |

Hybrid (Air Guard/Seal) | Excellent, near-zero discharge | Best of both worlds | Higher complexity, cost | Near-zero pollution |

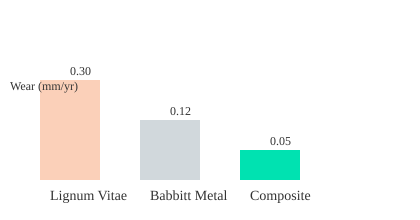

Typical Wear Rate Comparison

As technology advances, the oil vs water lubricated bearings debate continues to evolve, with each system offering distinct operational and environmental trade-offs. The industry’s shift toward composite water-lubricated bearings signals a strong move toward sustainability, while oil-lubricated systems remain unmatched for high-load, high-speed applications—if their secrets can be kept from the ocean’s relentless reach.

Green Pressure: How Environmental Regulations Are Reshaping Maritime Engineering

The backbone of modern marine engineering is no longer just about strength and efficiency—it’s about sustainability. Today, environmental regulations maritime engineering are driving a profound transformation in how ships are designed, built, and maintained, especially at critical interfaces like the stern tube. This shift is most visible in the adoption of Environmental Acceptable Lubricants (EELs) and the rise of innovative sealing technologies, all in response to a tightening web of global and national rules.

MARPOL Annex I, US EPA VGP, and VITA: Key Acronyms Driving Stern Tube Reforms

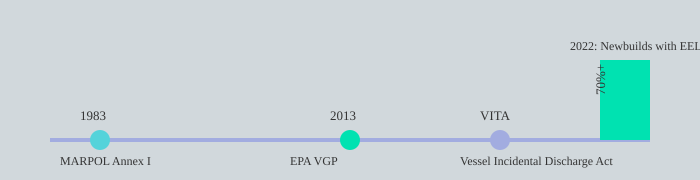

Three major regulatory milestones have shaped the current landscape:

MARPOL Annex I (1983): The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, targeting oil pollution and making oil-to-sea leakage a global concern.

US EPA Vessel General Permit (VGP, 2013): Introduced strict requirements for vessels operating in US waters, mandating the use of EELs or zero discharge at oil-to-sea interfaces like stern tubes.

Vessel Incidental Discharge Act (VITA): The successor to VGP, reinforcing and expanding compliance requirements for environmentally sensitive operations.

Mandate: Environmental Acceptable Lubricants (EELs) Now Required

The regulatory message is clear: only EELs—biodegradable, non-toxic lubricants—can be used where oil might contact the sea. For stern tubes, this means traditional mineral oils are out, and EELs are in. EELs are vital for compliance, especially in sensitive waters, but they come with operational challenges: they are typically 2–3 times more expensive than mineral oils and can be harder to source in bulk, especially in remote ports.

Chart: Timeline of Global Environmental Milestones Affecting Stern Tubes

Necessity is the Mother of Turbocharged Marine Invention

As regulations tightened, the industry responded with a wave of innovation. Double-sealing arrangements, AirGuard systems (using air barriers to prevent oil escape), and a return to advanced water-lubricated systems (now using high-tech composite bearings) are all direct results of compliance demands. As one regulatory advisor put it:

"Compliance is not a nuisance; it is a catalyst for smarter, greener ships." – Regulatory Advisor, Maria Feldman

Bulk EELs: Expensive but Essential for Sensitive Waters

For ships entering US or similarly regulated waters, EELs are not just a best practice—they are mandatory. This has led to logistical challenges, as sourcing and storing bulk EELs can be complex and costly. Still, with over 70% of newbuilds in 2022 featuring EEL-compliant systems, the industry is adapting rapidly.

Wild Card: Real-Time Compliance and the Future

Looking ahead, some experts envision a future where ships could be fined in real time for sensor-detected leaks, with data transmitted via AIS (Automatic Identification System). This would make compliance not just a design issue, but a continuous operational imperative, crowdsourced and monitored globally.

In summary, marine engineering sustainability trends are being shaped—sometimes forced—by environmental regulation. The result is a new era where eco-friendly lubricants, advanced sealing, and real-time monitoring are not optional, but essential for every ship’s backbone.

Quiet Geniuses: The Unsung Wonders of Modern Stern Tube Design

When it comes to innovations in stern tube design, the spotlight often shines on bearings and seals. Yet, the real genius lies in the entire system—a robust, multi-layered assembly where every component quietly plays a vital role in keeping ships moving safely and efficiently. As Systems Engineer Leon Kim puts it:

“You only notice the stern tube when something goes wrong—so we engineer it to go right, quietly, for a decade.”

Beyond Bearings: The Stern Tube’s Heavy-Duty Housing

The stern tube’s cylindrical housing is a feat of heavy engineering. Typically fabricated from steel with a wall thickness of 30–50 mm, it is welded directly into the ship’s hull, forming a watertight backbone. Precision is everything—laser alignment during installation ensures the shaft spins true. A misaligned housing can lead to years of vibration, noise, and expensive repairs, making this step critical for long-term reliability.

A Who’s-Who of Components: More Than Meets the Eye

Modern stern tubes are a showcase of component innovation. Here’s a breakdown:

Main Bearings: Support the propeller shaft, handle immense loads, and ensure smooth rotation.

Shaft Liners: Replaceable sleeves (often bronze or stainless steel) that protect the shaft from seal wear—replacement costs range from $10,000–$50,000.

Sacrificial Anodes: Blocks of zinc or aluminum that corrode in place of critical metal parts, replaced every 2–5 years.

Earthing Brushes: Carbon brushes that prevent stray electrical currents from “zapping” bearings—a little-known but vital defense against electro-etching.

Temperature and Vibration Sensors: Typically 4–8 per stern tube on large ships, these sensors feed real-time data to the bridge and engine room.

Stern Tube System Breakdown

Component | Function | Common Failure Cause |

|---|---|---|

Main Bearings | Support shaft, reduce friction | Wear, misalignment, lubrication loss |

Protect shaft from seal wear | Abrasion, corrosion | |

Sacrificial Anode | Prevent galvanic corrosion | Consumption over time |

Earthing Brush | Divert stray currents | Wear, loss of contact |

Temp/Vibe Sensors | Condition monitoring | Sensor failure, wiring issues |

Why Carbon Brushes Matter: The Hidden Threat of Stray Currents

Few realize that stray electrical currents can silently damage bearings through a process called electrical discharge machining—essentially micro-sparks that pit the metal. Carbon earthing brushes provide a safe path to ground, preventing this hidden threat and extending bearing life.

Condition Monitoring: The Engineer’s Midnight Dashboard

Condition monitoring marine systems have transformed stern tube reliability. Temperature and vibration sensors deliver real-time alerts—typically 3–10 per voyage—enabling predictive maintenance in maritime operations. Imagine an engineer, woken at midnight by a dashboard alert: a sudden temperature spike in the aft bearing. Thanks to these smart systems, the issue is caught early, preventing catastrophic failure and costly downtime.

Innovations in stern tube design now depend as much on these “quiet geniuses”—the shaft liners, anodes, earthing brushes, and smart sensors—as on the bearings themselves. Each component, though unsung, is essential to the stern tube’s role as the ship’s silent, steadfast backbone.

Clash of the Titans: When Oil, Water, and Air Designs Compete

In the world of stern tube engineering, three main contenders dominate the conversation: oil lubricated bearings, water lubricated bearings, and the increasingly popular air guard systems for ships. Each system has its loyal advocates in shipyards and boardrooms alike, and each represents a unique balance of tradition, innovation, cost, and compliance. As one seasoned fleet manager, Karl Weng, puts it:

“There’s no perfect system, only the right answer for the right ship on the right route.”

Oil-Lubricated Bearings: The Reliable Workhorse

Oil-lubricated stern tubes have long been the industry standard. Their appeal lies in a stable, proven design that delivers excellent shaft support and long service intervals—typically 7 to 12 years between major overhauls. The hydrodynamic oil film minimizes friction and wear, making these systems ideal for large merchant vessels and tankers operating at high loads and speeds.

However, the Achilles’ heel of oil systems is environmental risk. If seals fail, oil can escape into the sea, triggering regulatory headaches and potential fines. Even with environmentally acceptable lubricants (EALs), the risk of discharge remains a concern, especially under today’s strict compliance regimes.

Water-Lubricated Bearings: The Eco Champion

Modern water lubricated bearings have come a long way from their lignum vitae ancestors. Today’s systems use advanced composites and polymers, offering zero oil discharge and full compliance with the toughest environmental rules. They are especially favored for ferries, cruise ships, and vessels operating in sensitive waters.

Yet, water systems are not without quirks. They demand clean, filtered water to prevent abrasive wear, and can be more sensitive to alignment and low-speed vibration. Maintenance intervals are slightly shorter (5 to 10 years), and initial costs are 20–30% higher than oil-based systems. Still, for many operators, the environmental peace of mind is worth the trade-off.

Air Guard Systems: The Hybrid Hero

Enter the air guard system—a hybrid innovation that combines the best of both worlds. Here, oil remains inside, but a pressurized air barrier prevents leaks from reaching the sea. Any oil that does escape the inner seals is captured and safely disposed of. These systems are technologically advanced, requiring compressors and monitoring equipment, which raises both capital and maintenance complexity. But with mean times between overhaul often exceeding 10 years and environmental risk reduced to near zero, air guard systems are gaining traction, especially for newbuilds in regulated markets.

Comparing the Titans: Key Trade-Offs

System | Capital Cost Index | Maintenance Complexity | Mean Time Between Overhaul | Environmental Risk | Typical Vessel Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Oil-Lubricated | 1.0 (baseline) | Moderate | 7–12 years | High | Bulk carriers, tankers, container ships |

Water-Lubricated | 1.2–1.3x | Low–Moderate | 5–10 years | None | Ferries, cruise ships, eco-sensitive vessels |

Air Guard | 1.4–1.6x | High | 10+ years | Minimal | Newbuilds, high-compliance fleets |

A Fleet Manager’s Dilemma

Fleet managers often find themselves weighing these options with a heavy sigh. The debate is rarely just technical; it’s a nuanced act of balancing operational reliability, upfront investment, maintenance demands, and the ever-tightening grip of environmental regulation. As Karl Weng notes, “There’s no perfect system, only the right answer for the right ship on the right route.”

Ultimately, the choice between oil, water, and air guard systems reflects the evolving priorities of modern shipping—where innovation, tradition, cost, and compliance all have a seat at the table.

When Good Tubes Go Bad: The Many Faces of Stern Tube Failure

For all their hidden strength, stern tubes are not immune to trouble. When failures strike, they can escalate from minor leaks to full-blown operational crises, costing time, money, and sometimes even the ship’s environmental reputation. Understanding the main stern tube failure modes—and spotting their warning signs early—is essential for every modern vessel operator.

Seal Degeneration: The First Clue is in the Water

Seals are the stern tube’s frontline defense, keeping lubricants in and seawater out. But they’re also its most vulnerable point. Over time, seals degrade due to friction, age, and debris. The earliest sign? A telltale rainbow sheen on the water’s surface—a clear indicator that oil is escaping. According to global fleet data, mild leaks occur in about 0.3–0.7% of vessels per year. Left unchecked, a small leak can quickly become a major headache, contaminating the ocean and risking regulatory fines.

Bearing Wear: The Sneaky Destroyer

Bearing wear is a silent threat, often caused by dirty oil, abrasive sand, or simple bad luck. When lubrication fails—whether due to contamination or low oil levels—metal-to-metal contact increases, accelerating wear. Symptoms include rising bearing temperatures and abnormal vibration patterns, both detectable through condition monitoring marine systems. If ignored, bearing wear can escalate to catastrophic shaft damage, with unplanned stern tube repair costs ranging from $50,000 to over $300,000.

Shaft Misalignment: The Silent Killer

Shaft misalignment is a less visible but highly destructive failure mode. It can result from poor installation, hull flexing in rough seas, or gradual structural changes over time. Misalignment places uneven loads on bearings and seals, leading to rapid wear and vibration. The average downtime to correct misalignment is 3–7 days—a costly delay for any commercial vessel.

Stiction and Noise: The Water Bearing Challenge

Modern water-lubricated bearings offer environmental benefits, but they introduce unique challenges. At slow speeds, these systems can experience “stiction”—a stick-slip phenomenon that causes creaking noises and vibration. While not always immediately damaging, persistent stiction can accelerate wear and affect propulsion efficiency, making predictive maintenance maritime operations even more critical.

Chart: Common Stern Tube Failure Modes and Warning Signs

Failure Mode | Visible Signs | Technical Symptoms | Operational Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

Seal Degeneration | Oil sheen on water | Oil/water in wrong compartment | Environmental risk, fines |

Bearing Wear | None until advanced | High temp, vibration | Potential shaft damage |

Shaft Misalignment | Vibration, noise | Uneven wear patterns | Extended downtime |

Stiction/Noise | Creaking at low speed | Irregular vibration | Reduced efficiency |

Wild Card: When Disaster Strikes Far from Shore

Imagine both primary and backup seals fail—1,000 km from the nearest port. Oil leaks out, seawater floods in, and the shaft is at risk. Emergency protocols kick in, but the vessel faces immediate speed restrictions and must divert for urgent repairs. The financial and reputational costs can be staggering. As Chief Mechanic Elena Torres puts it:

"You plan for perfect, but it’s the sea—sometimes nature throws a wrench."

With seal replacement intervals ranging from 3–7 years (oil/water) to 5–10 years (air systems), and the high cost of unplanned repairs, the value of robust condition monitoring marine systems and predictive maintenance maritime operations cannot be overstated. Early detection is the difference between a routine fix and a high-seas disaster.

The Future of Stern Tube System Engineering: Where Tech and Sustainability Collide

As the shipping industry faces mounting pressure to reduce its environmental footprint and maximize operational efficiency, the world of stern tube engineering is entering a new era—one where technology and sustainability are inseparable. The stern tube, often compared to a ship’s “kneecap”—vital but largely unnoticed until trouble strikes—is now at the center of marine engineering sustainability trends. Innovations in stern tube design are rapidly transforming this hidden interface into a showcase of green technology and predictive intelligence.

Today, the push for greener, safer, and smarter ships is reshaping every aspect of stern tube systems. Environmentally acceptable lubricants (EELs) are becoming the default, driven by international regulations and a global commitment to cleaner oceans. By 2030, it’s projected that over 90% of large vessels will operate with EEL or air-seal systems, drastically reducing the risk of oil pollution. This shift is not just regulatory—it’s technological. Advanced composite bearings for ships, made from high-performance polymers and reinforced materials, are replacing traditional metals. These composites offer superior wear resistance, lower friction, and the ability to operate with seawater lubrication, eliminating oil discharge entirely in many cases.

But the most profound change is happening in how these systems are monitored and maintained. The future is predictive, data-driven, and nearly invisible to operators. Smart bearings embedded with IoT sensors now continuously track temperature, vibration, and lubricant quality. This real-time data feeds into sophisticated analytics platforms, often powered by artificial intelligence, enabling truly predictive maintenance for maritime operations. Instead of waiting for a failure, ships can now anticipate issues—reducing downtime by up to 25% and saving millions in emergency repairs. As futurist engineer Priya Anand puts it,

“Tomorrow’s ships will whisper back when they need care, not scream for rescue.”

This transformation is already reflected in the market. The global smart sensor market in shipping is expected to surpass $2 billion by 2028, signaling widespread adoption of these technologies. The chart below illustrates the projected adoption rate for smart stern tube systems through 2030:

Year | Projected Adoption Rate (%) |

|---|---|

2024 | 55 |

2026 | 70 |

2028 | 82 |

2030 | 93 |

This new era also demands a new breed of marine engineer—one as fluent in traditional mechanics as in digital analytics and sustainability. Today’s maritime education blends the fundamentals of shaft alignment and bearing design with the latest in sensor integration, data interpretation, and green technology. The next generation is being trained to see the stern tube not just as a mechanical component, but as a living, data-rich system at the heart of a ship’s environmental responsibility.

Looking ahead, the horizon is wide open. Imagine a future where stern tubes are not only smart but self-healing—using adaptive materials that respond to wear, or microfluidic systems that adjust lubrication in real time. What if the stern tube could repair itself, or even signal for help before the first sign of trouble? As the industry continues to innovate, the stern tube may soon become the most quietly revolutionary part of the ship—protecting both propulsion and the planet, one voyage at a time.

TL;DR: Stern tube systems are a marvel of marine engineering, evolving from wooden solutions to modern eco-friendly technologies. Their hidden design keeps ships running smoothly, protects our oceans, and inspires ongoing innovation. Whether you’re a seasoned pro or a curious newcomer, understanding stern tube systems means seeing the backbone of shipping—and its future—in a whole new light.

Comments

Post a Comment